Archeologist, Educator, Historian and Author

Victoria El Henawy as a kid always had her knees in the dirt, so it came as no surprise to her mother when she decided to study archaeology. The daughter of British immigrants to the US, Victoria graduated with a degree in Islamic Art and Architecture from the SOAS, University of London where she chose to specialise in 12th to 15th-century Egypt. Her love for the country, culture, and its people, is the reason Egypt will always be her adopted home, says Victoria. Currently, she teaches business english at the French International School of Hong Kong and is a Teaching Assistant and Researcher at the University of Hong Kong. And the title most recently added to her long list of accomplishments is that of “Author.”

We sit with Victoria to talk about her passion for Egypt, her work as a women’s rights advocate and her new book.

Did you always want to be an archaeologist, and how did you get interested in Islamic Art and Architecture living in the US?

Always. You know, I was the kind of girl who was always outside, always up a tree. I loved the outdoors and knew an office job would stifle me. This field excited me. I worked at the British Schools of Archaeology in Jerusalem, and after graduation, I got a full-time job with them. While in Israel, I studied under a rather famous archaeologist, Gabriel Barkay, who also became my mentor. He guided me towards Islamic art and the Islamic period in history.

Growing up, who were your inspirations and role models?

Growing up, one of my favourite things to read was National Geographic. I had a love of travel and an appreciation of other cultures from a very young age. I found Joy Adamson, a European woman who moved to Africa, very fascinating. My mother was also a real pioneer, which is one reason I decided to step it up with my daughter.

C – The Tree of Pearls

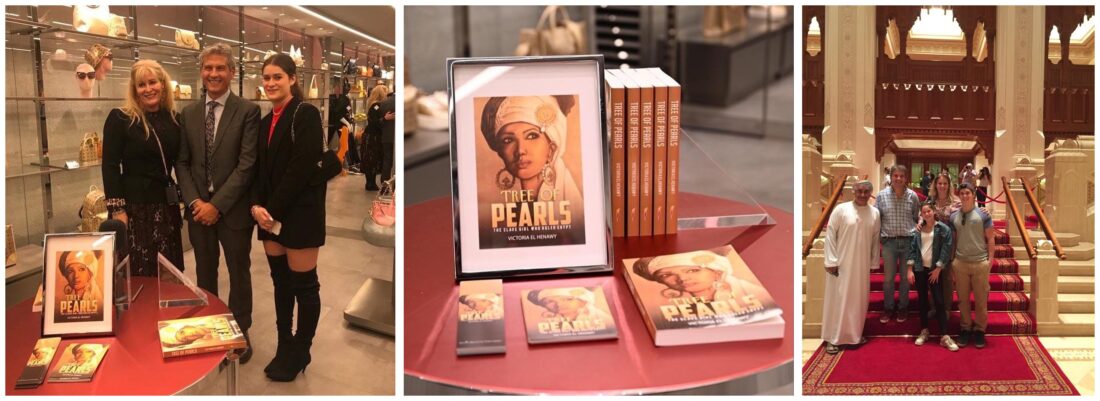

R – Victoria and her husband with their children.

Please tell us about your work with various charities supporting women’s rights over the years. How did architecture lead to activism?

I met my husband, a diplomat, when I was in Egypt. After marriage, I left my work as an archaeologist, and during that period, I was introduced to a French charity, L’Afam, started by a friend who worked with Yazidi women in Iraq. The Yazidis are a dying culture and have faced the most horrific things at the hands of the ISIL. I remember many of our friends being quite surprised and questioning my husband why he was okay with his wife going to Iraq. He knew as I did, I needed that experience as much as the Yazidi women needed me.

Every single one of the women I met said they were so blessed and lucky. I was there with them, and in my mind, the truth couldn’t have been further from that. Hearing their stories, I kept thinking nothing could be worse, but they all said they were lucky because they survived and were alive. I needed to hear that at the time.

That is why it is so amazing when women help women. I never go with the attitude that I’m there to help anyone. I got as much from them as they got from me. I needed them to tell me how lucky they were because I needed to hear that. Some days we can help with money, some days with listening and empathy, and some days it helps them to know that they are helping us too.

I write this in my book too. Men are the ones who often start and go to war, and it’s always the women who suffer the most. They lose their sons and husbands, they get raped, and they were never the ones who started the war in the first place.

When did the idea of a book first come to you, and what motivated you to write it?

A few years ago, my teen daughter was being picked on, and I saw her struggling with her muslim identity to the extent that she told people her father was Brazilian and not from the Middle East. She didn’t want us to speak Arabic in public or identify with her Egyptian culture; she didn’t want to acknowledge that her father is a muslim.

It was a real aha moment for me when I saw her struggling with who she is and her self-confidence. I knew I had to do something. We had a problem, and I wanted her to embrace her identity and be proud of it, not ashamed of it.

Girls like my daughter grew up thinking that you can achieve anything if you’re white and christian. When my daughter was in school in Egypt, they were introduced to many inspiring women, but they were all white women, and I would think to myself, even then, where are the stories about brown, muslim, Egyptian women? While this may sound strange since I’m British and white, my daughter isn’t.

I was familiar with the story of Shajara al-Durr for many years. Our family lived in Egypt, and she is a very well-known character there. There is food and streets named after her. She was an extraordinary muslim woman, a slave girl and a foreigner who ruled Egypt in the mid-13th century. I felt her story would be relatable to girls like my daughter. I was also intentional about the cover of my book and was clear from the very beginning that I wanted an Egyptian woman artist. It is so important for our daughters to be self-assured and confident and proud of how they look and accepting of their culture. And we must show them role models they can look up to, who look and speak like them.

Virginia Woolf said, “For most of history, Anonymous was a woman”. So much of women’s history is lost and unaccounted for. Why is it important to uncover, explore and share some of these stories?

It’s incredibly important that women tell their stories. We see them from a different perspective. There are stories written about Shajara, but she’s not put in a good light. Even in movies, she’s been portrayed as bad. Women need to tell these stories from their perspective. For so long, women were anonymous, and they could only tell their daughters their stories. I am a true believer in women supporting women and for us to support ourselves. Ultimately, we live in a patriarchal system, and we have to believe in ourselves and lift others.

Through my studies and work experience, the one thing that I have learnt is that history repeats itself. We see that currently happening with women’s rights in the US, Afghanistan and Iran. Megalomaniacs have led to the downfall of many empires, and we still have megalomaniacs ruling the planet. Young people must see the similarities and not just the differences in cultures. The more I experience different cultures and live in other countries, I’ve realised that people are actually more similar than different. But human nature is prejudiced, and working together can make us stronger. And it cannot be accomplished without the empowerment of women.

What do you want your readers, especially young girls, to take away from your book?

That anything is possible. I genuinely believe with faith and education, women can accomplish great things.

Can you share anything about your future writing projects?

I had this great dream of doing a series of inspirational books with women from different religious backgrounds and cultures. Right now, I’m unsure about when the next book will be. I am inherently a storyteller, and we need inspiring stories about women. I want to get my current book into the Egyptian and International school systems. A true story about a slave who became Queen of all Egypt, this book could change how girls think about their Arab heritage as it did with my daughter. Through education, great things can happen.

Finally, how do you take your coffee?

I have a special type of blend of coffee. I do half Turkish, which is Arabic coffee with cardamom, and I mix that with some regular coffee because I don’t want it to be too strong. I like just the tiniest bit of cold milk, some almond milk usually. I hate the taste of hot milk. Hot and frothy, I cannot stand (laughing).

“…people are actually more similar than different. But human nature is prejudiced and working together can make us stronger.” This – and the challenge that it cannot be accomplished without the empowerment of women is a mighty call to action. Reading about Victoria and her incredible work was empowering.