Spanning Europe and Asia, at the heart of Turkey’s magic is its eclecticism and plurality. This summer, I visited Turkey for the second time and spent an evening watching whirling Dervish and traditional folk dances at Hodjapasha, where I saw this eclecticism embodied.

On my first visit to Turkey around 20 years ago, I saw the Dervish sema dance ritual in a strange cellar-like venue with domed ceilings of rough bricks painted white and dark, with varnish-stained wooden furniture. I remember being interested in the ceremony but not really understanding it. Twenty years on, and having read the poetry of Rumi and Hafez, the novel “Forty Rules of Love” by Elif Shafak about the transformative friendship between Rumi and the Dervish monk Shams, and having had some experience with Sufi spiritual communities, I was a little bit more ready to receive and appreciate this mesmerising ritual.

Thesema begins with sung prayer and music. Then the dancers enter, kneel in prayer, move into the central floor space and slowly start spinning. Beginning with their arms crossed over their chests and their heads gently tilted to one side as they rotate, the dancers unravel their arms, their elbows rising, arms unfolding outwards and upwards until they are extended with one hand facing upwards towards the sky and the other down to the earth. As their arms unfurl, so do their skirts, gently lifting as they spin, rising out and rippling and undulating as they turn. In this position, they spin steadily in place, the left foot planted on the ground as

the right heel-ball-toes pushes them around in a complete turn. After a few minutes, they then begin to orbit the space in a counterclockwise direction. Then, gradually, the dancers slow down, drawing their arms back in, their skirts lowering, as they return to a stationary standing position. This part of the ceremony repeats several times, the pattern remains exactly the same, the pace of the spinning increasing with each repetition as they go through a process of rebirth and embodiment of shedding their ego. The sight is hypnotic, with layers of whirling skirts, arms, bodies on their own orbit and bodies orbiting the space. Watching them, you feel a sense of calm in your own stillness relative to their movement.

On the same evening that I saw this show, I also watched a display of Turkish folk dances. While the show was light-hearted in comparison, the dances themselves were highly eclectic and fascinating to watch. The show included male and female belly dancing, which are performed separately. I’ve done belly dancing before and have some basic familiarity with the moves, but while I’d read about the male dance, I’d never seen it. What was interesting was that both versions were identical in all but their energy: the men’s dance involved exactly the same rolling, shimmying, undulating sensuality as the women’s dance, but the male

energy was more powerful and the female energy more delicate. Ultimately, both versions celebrated the body, its energy and vibrancy!

Some dances were performed separately by the male and female dancers. One female dance included the graceful use of fans, reminiscent of East Asian dances, while in another, the women wore elaborate candelabras wrapped around their turbans, albeit lit with electric candles. They moved with slow, controlled undulations, performing feats such as sinking to the floor and rising up again, all presumably originally executed while not letting the candles go out or spilling a drop of wax. I’ve no idea if the dance was authentic, but it was fascinating.

The men’s dances included Zeibek, with its high leaps and kicks, punctuated with low dips tapping a single knee to the ground; powerful, energetic and vibrant, a clear embodiment of masculine energy. We were also shown a solo male dancer performing a fire dance and another a contemporary take on the dervish ritual in which the inner struggle of the dancer to cast off their ego was seemingly represented in the lifting and removal of the skirt. For some folk dances, men and women danced together. The movements included joyful stepping patterns, low kicks and spins, hands on hips or arms raised high, couples circling one another, or larger groups forming circles and lines. While varied in form, these dances were simple, energetic, and vibrant representations of fishing, harvests, and courtship and offered embodied celebrations of traditional life.

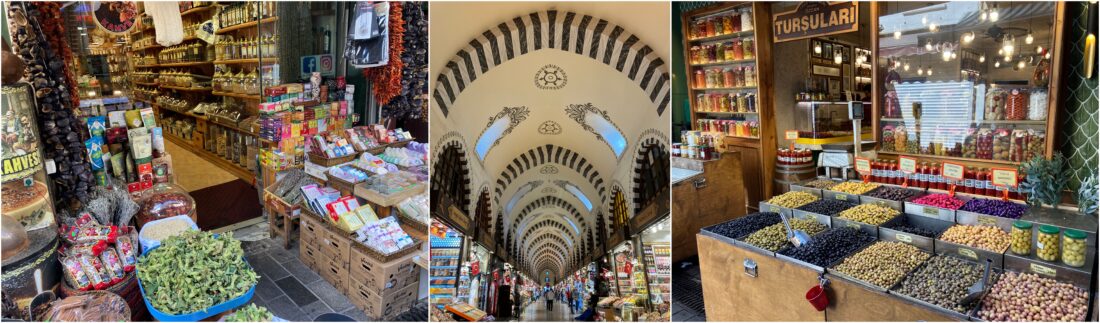

What characterised the dances and the evening was the wide variety in the music and movements: the different permutations of the folk and traditional dances and, of course, the Sufi Sema. Whether intentional or not, the variety offered awareness about Turkey’s long cultural history, a country positioned even now between Europe and Asia. When I visited the different bazaars in Turkey and saw the spices, teas, sweets, fabrics, jewellery, and other goods on offer, I was reminded that my experience was probably similar to what shoppers would have seen on sale here for hundreds or thousands of years, albeit arriving by a very

different journey.

Through the decades, Turkey has seen visitors and settlers from all over the world, from all walks of life and social standing, meeting and interacting on its streets. Like Cordoba in Spain in the 12th Century, 16th-century Lisbon, or London, Turkey was full of people from elsewhere, trading, cooking, making music, singing and dancing. Many travellers contributed to the unique blend of cultures the country still offers today, and much of it is reflected in its vibrant and varied arts, food, music and dance.

Juliette O’Brien PhD

Juliette is an avid and widely experienced dancer who loves to travel. She has a PhD in Dance from the University of Hong Kong and is a teacher of dance, drama, English literature and yoga as well as being a mum of two.

Sounded fun… I visited too this summer with my mother, it was preetty noice