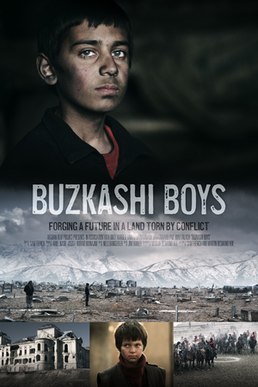

I remember when I was a kid, the BBC Farsi radio station (we hadn’t bought a TV yet) announced that the movie ‘Buzkashi Boys’ had been nominated for the OSCARS. Unfortunately, though the movie didn’t win, I still yearned to watch it. I even had the opportunity to borrow it from a friend, but it couldn’t work out. Years later, when I came across the movie once again, I had lost some of my interest by then. That is, until last night when I finally watched it.

Expecting the movie to be at least an hour long, it turned out to be just 30-35 minutes. ‘Buzkashi Boys’ is about two Afghan children, Rafi and Ahmad. Rafi is the son of a blacksmith, and Ahmad is a Spandi. A Spandi is a child who gets paid to bless people by burning an herb called Spand, which is widely available in Afghanistan. The smoke from the herb supposedly wards off misfortune.

Ahmad is extremely eager to become a jockey and he takes Rafi everywhere he goes even though it’s hard for the latter to get his father’s permission. To get his father to agree feels like going through the seven adventures of Rostam (the mighty knight from Shahnamah) for Rafi as his father always refuses initially, before allowing him to go with Ahmad.

Even in the midst of Kabul’s freezing winter, they go to watch a game of Buzkashi (the national sport of Afghanistan where horse-mounted players attempt to place a goat carcass in a goal). Winter doesn’t affect the people who chase the game with pleasure and jubilation. Ahmad, who knows much about the game, explains to Rafi what’s going on on the pitch.

In the movie, after watching the game, the boys go to visit the ruined palace of Dar-ul-Aman, where they speak of their dreams. Ahmad wants to become a jockey and Rafi, following tradition, wants to become a blacksmith like his father. Rafi criticises Ahmad’s dream and refuses to listen.

Later, we see Ahmad ascending a steel ladder to reach the roof of the palace, while Rafi, who is afraid, stays where he is. Ahmad reaches the top of the roof, takes a green handkerchief out of his pocket and shouts out, “My name is Ahmad, son of Abdullah; I want to become a jockey.” Rafi hears him, but to him Ahmad’s declaration is nothing more than a dream because Ahmad needs a horse to become a jockey, which he doesn’t have. Rafi reminds Ahmad of this many times. Later in the movie, Ahmad finds a horse that is dark red in colour. He rides the horse but sadly falls off and dies. Rafi is heartbroken about losing his friend and returns to accept the blacksmith’s job, one that is a lifetime duty for him.

Accepting this job, he fulfils his destiny of becoming a blacksmith. The movie ends here, leaving the spectator with disappointment.

I was surprised by the connection I found between the narrative of Rafi’s life in the movie, and the current real life of many Afghans. For me, the movie didn’t even merit the silver Simorgh of the Iranian film festival (the Fajr Film Festival), but conceptually, it has many things to say.

We’ve been fighting a 50-year war, and even our (so-called) educated and intellectual characters count on our outdated resistance against Great Britain, Russia and America. So many of us honor the past just like Rafi honoured his ancestral occupation as a blacksmith. An occupation that has been passed down generations from his grandfather to his father because it is a respectable occupation. We are the same; many of us honor war, because we think war has brought us respect and honor in the global community. We honor our wounds. We destroyed the whole country, but we have no (not even the smallest) achievement, be it scientific, political or financial, that can be appreciated by the international community. Some Afghans honor their ‘ancestral occupation’ and have accepted war, terror and Jihad as their destiny. They are timid like Rafi, not mighty like Ahmad, where they shout out their names and dreams. A loaf of bread and a subsistent salary are enough for some, but they don’t seem to want more than that.

Ahmad, for me, symbolises the dreams that many Afghans have of peace, empowerment and development. Rafi, on the other hand, represents the harsh truth of much of Afghanistan: fear, no self-confidence, no risk-taking and obedience. Our rebellion is just good for war, and maybe that’s why we have professional generals and partisans, but we look to other countries for skilled people in other fields. Maybe for people who dare to dream like Ahmad but have timid hearts like Rafi, it’s better to stay low. There is always a risk of falling off the horse and dying, so some will find it better to stay low.

Sam Franch, the American director of the movie, probably understands what Afghans are afraid of the most. But instead of making a documentary that addresses us in a straightforward manner, telling us that the time of Jihad and war has passed and that times have changed, he conveys the message through the story of two Afghan kids and Afghanistan’s national sport, Buzkashi. His script shows us a child consumed by his dreams and another struggling with his reality.

The movie left me wondering if it’s possible at all for us to become jockeys like Ahmad, even if there is a risk of falling off the horse and dying. Will we ever see the day, where even for just five short years, we taste the sweetness of development, be honored by the international community, and have enough power and courage to take charge of our lives? Is it even possible for us, especially those who have been living their lives like Rafi for years, to dare to ride the horse of development, ride it and take it towards a better future?

Farid Ahmadi

Farid Ahmadi has been writing stories since his childhood. Luckily he had access to many books in multiple genres, which helped him delve deeper into English literature. One of his fondest memories is of his story, The Blue Eyed Girl being published in his high school magazine, and being well received both by the students and instructors.

After graduating high school, Farid had two options: to study in a university in Kabul under a broken system under the Taliban, or work and self-study. He chose the latter.

Contact – faridk.ahmadi5@gmail.com