I learnt about the journalist writer Chander Suta in the winter of 2021. At the time, India was celebrating 50 years of its victory in the Indo-Pak war of 1971, and I was delving into the story of the ‘Missing 54′. The timing was not a coincidence.

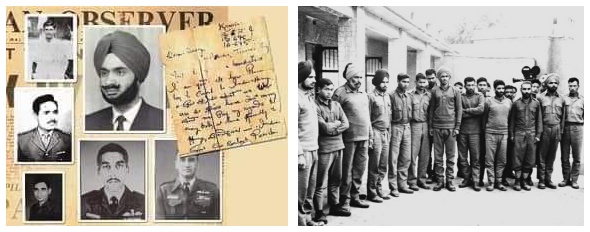

The ‘Missing 54’ are soldiers of the Indian Armed Forces who were declared “missing in action, presumed dead” in the ’71 war. Five decades later, their status remains unchanged.

It is a travesty and a tragedy that a war fought to liberate a country, left 54 of its liberators as prisoners of war till the end of their known lives. Even more shocking is the fact that the onus of providing “proof of life” was left to the distraught families and the missing men themselves.

Imagine this. A grieving family receives a letter from their son, three years after being told he was “killed in action”. Then, the following year a second letter arrives. And he writes, he’s in a jail in Pakistan with 20 other POWs. The handwriting is of Maj AK Suri, SS-19807 (5 Assam).

Cut to the present day almost 52 years later. Their existence all but forgotten by successive Indian governments, the #missing54 (now a hashtag) are only known through the stories of their relatives who refuse to give up. One of them is a friend, Dr. Simmi Waraich, who has spent her entire life looking for her father, Maj SPS Waraich, IC-12712 (15 Punjab).

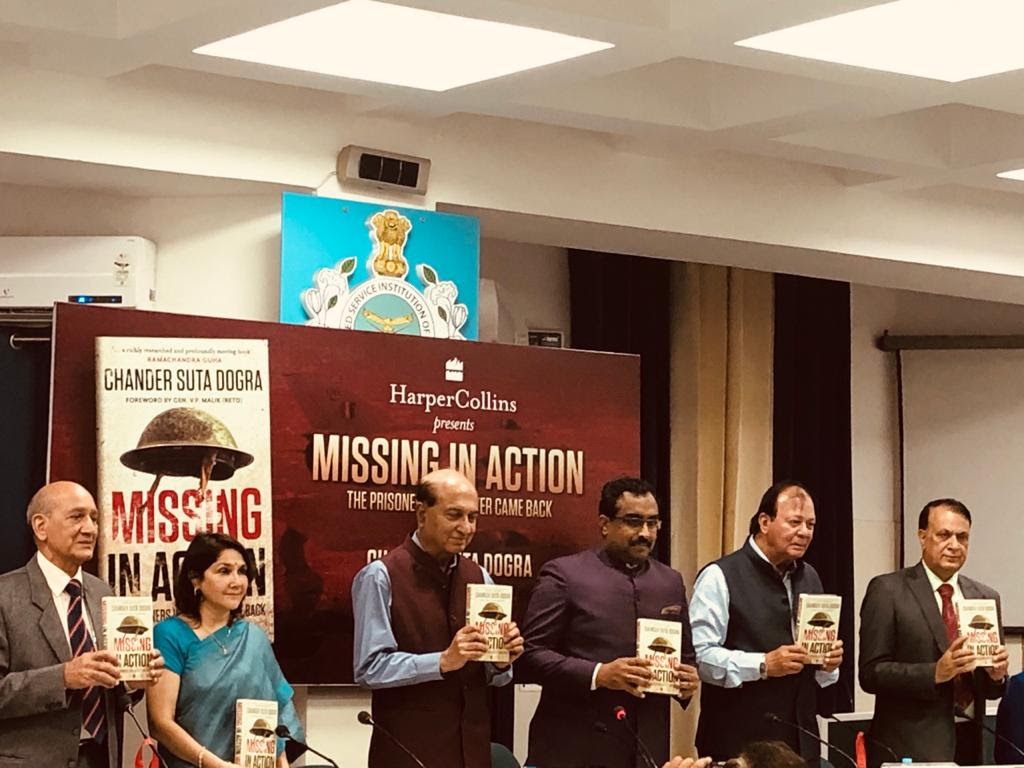

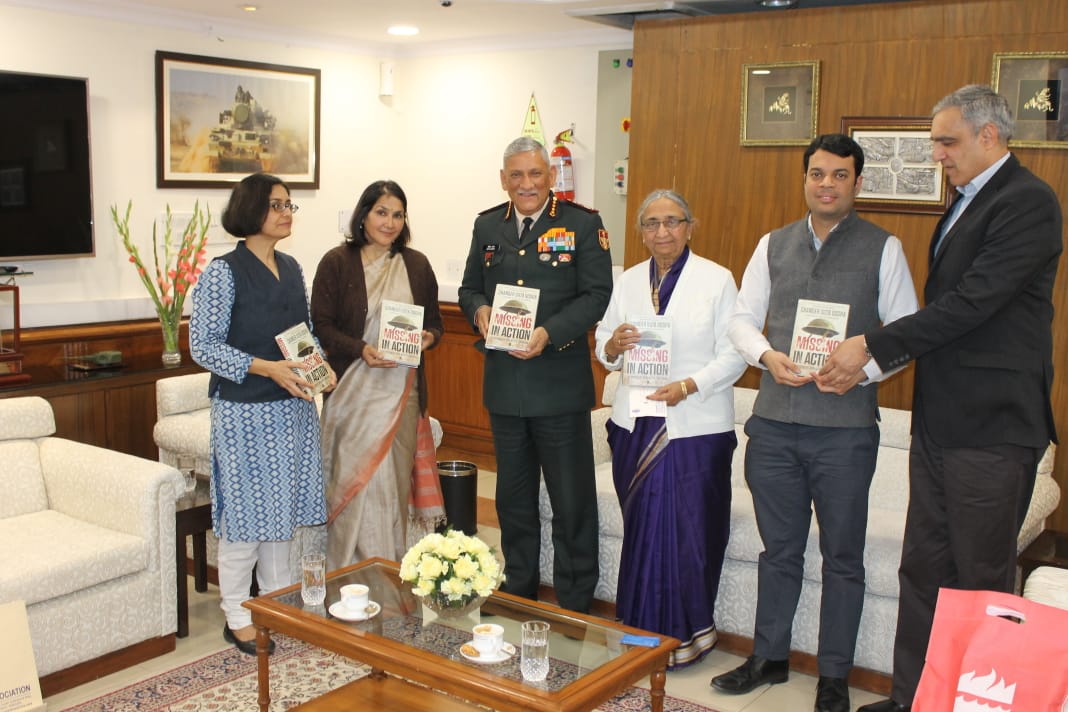

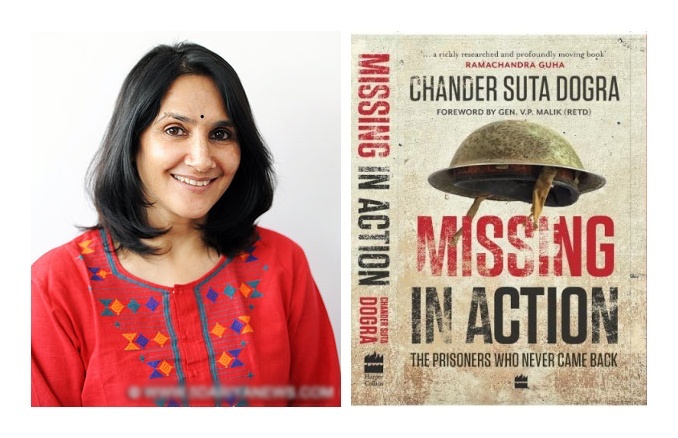

These stories about the ‘Missing 54’ and the lifelong fight by their families are among those documented by Chander Suta in her seminal book, ‘Missing In Action: The Prisoners Who Never Came Back’. Extensively researched over a period of several years, the book attempts to answer the key question – what happened to these men?

That’s what I wanted to know when I reached out to the journalist writer. Chander Suta, as I discovered, is a woman who wears her many hats to perfection, and with a passion. Her belief, “When you love what you do, it doesn’t feel like work”, is at the core of everything she does. As a senior journalist, published author, organic farmer, Himalayan car rally driver and avid trekker – the common thread that runs through it all is her self belief, passion and resilience.

Suffice to say, I was more than inspired. Read below, an excerpt of my conversation with Chander Suta.

Let’s go back to the beginning. When did you know that you wanted to become a Journalist?

Oh, I think it was in school when my English teacher read out my essays before the class. That was a time when I thought that journalism is all about writing. It is only later that I learnt that turning in a good, clean copy is only one half of the job. How well you can source your information, collate the facts and put them together in a coherent manner is the other, more challenging half. By the time I graduated, I was sure that I wanted to be one, but my parents had other plans. Marriage was on the cards and not a journalism degree that I dearly wanted to acquire. Nevertheless, the bug had infected me well and proper, and through the initially busy years of babies and feeding bottles, I managed to write a few articles that got published in newspapers and also a couple of short stories for children. Once the children began going to school, I landed my first job with the Indian Express in Chandigarh, and never looked back.

When and where do you like to write?

I have been a professional journalist for the last thirty-odd years, which means that I have been writing for a living. Mainstream journalism is all about crazy deadlines, researching stories and reaching out to all kinds of people to gather information. One doesn’t have the luxury of deciding when and where to write. When there is a story, you just go out there and do it. I have written news reports sitting in a car and tapping out the words on a portable typewriter once when there was firing happening outside a hotel in Kashmir as I struggled to meet a deadline. But generally, I like to write late at night when all is quiet and I can gather my thoughts and pursue the threads that I need to.

You have written two books, ‘Missing In Action: The Prisoners Who Never Came’ and ‘Manoj And Babli: A Hate Story’. Both of your books came with a lot of research. What does your research process look like?

My books are more from a journalist’s pen and not academic works. So, the research comprises good old reportage, exhaustive interviews, and digging into old records, letters, files and more. I lay stress on cross-checking each and every detail that I put into the pages. When I did my first book ‘Manoj and Babli – A Hate Story’, my publisher Penguin India told me to follow the ‘faction’ style of writing – a blend of fact and fiction – to make it more readable. But I just could not compromise on facts. Even the colour of the kurta – green – which Babli wore on the day she was murdered was authenticated from court records. I only recreated the atmospherics like muggy monsoon weather, the smell of fear in the family, helplessness, desperation or descriptions of the countryside based on what I had seen during several visits to their village in Kaithal district.

How long did it take you to write Missing In Action?

This was a long project that took several years. The writing itself took about two years to complete. But it was the research that was time-consuming, mainly because after a gap of more than 40 years many of those who participated in India’s wars with Pakistan -1965, 1971- had either passed on or retained a hazy memory. So, to find alternate sources of authentic information, persuading them to open their memory chests and fix appointments according to their availability took time.

What was the most difficult part of writing it?

I think that collating the voluminous information in the form of records, old articles and newspaper clippings, letters and video recordings of interviews was the most challenging. Files, books, and papers would be strewn for days on tables, chairs and everywhere else in my little cottage in the hills. Persuading the family to ignore the mess and avoid it if possible also took some tact. Often, in the midst of writing a chapter, I would realise that I needed additional facts to buttress a line of thought, which meant shelving it for a few days to do some more research.

The little cottage in the hills is more than just your writing retreat. It’s also where you manage your orchard. How did the move to becoming an Agriculturist come about?

I acquired this little farm in the hills during the years when I was actively touring the north Indian states for work. The cottage came in handy when I began writing my first book on honour killings, ‘Manoj and Babli- A hate story’. When I moved full-time to the farm to write my second book, ‘Missing in Action: The Prisoners who never came back’, I utilised the period to simultaneously establish an apple and plum orchard on the vacant land. By the time the book was launched, the orchard was well on its way and today, it has become my second passion after writing. My daughter named it ‘Devdar Orchard’ after the Cedar trees that line its edges. I grow a variety of fruits like apples, plums, peaches, apricots, kiwis and some vegetables too on the land.

There’s more. Tell us about the podium finish for your all-women team at your very first car rally, the Raid de Himalaya.

These things just happened as life cruised along. Before I participated in the Raid de Himalaya car rally, I had gone to cover it the previous year as a journalist. The drivers and participants were having way more fun than us sitting in our comfortable cars. By the time I returned, it was a given that I would be among the participants the next year. A college friend of mine joined up, and we got some funding to pay for the entrance fees and other expenses. My father’s relatively new Maruti Swift was quickly fitted out with new tyres, a set of snow chains and a steel underplate. Even before the rally began, I broke the front fender in a crowded market in Shimla, where we had been sent by the organisers to buy helmets. The Raid’s safety and scrutiny standards are rigorous. The broken fender was roughly held up with some screws and strings and though shaken by the early mishap, we reached the flag off point the next morning, still determined to brave the Ladakhi mountains.

As we drove through the rough mountain roads, some treacherous, some snowy, all that played in my head was my friend and rally guru Kishie Singh’s advice, “Whatever may happen, never let your car break down. You may be trailing but if your car is fit, you are in the race.” I saw battered SUVs driven by recklessly enthusiastic drivers parked on the side of remote mountain roads with their axles or suspension broken after crashing into a boulder, or drivers furiously replacing torn tyres. I took care to take my little Swift one stone at a time on the really rough patches. There were times when we found ourselves driving on dark mountain roads because all the others had gone ahead and reached the night halt. Our beginner’s luck held till all three – my car, my co-driver, and myself, reached Srinagar in one piece. The trophy that we won in the all-women category is my prized possession.

Your trek to one of the most remote areas of Ladakh is truly inspiring. What was that experience like?

The solo trek to Markha valley also happened with the flow of things. My husband was posted in Nimu, a small military outpost some 30 kms away from Leh. Nimu is situated at the confluence of the Indus and Zanskar rivers. I had heard of the Markha valley trek and since the valley across the Zanskar was quite close to where we were staying, I just had to go there. No roads led to the valley at that time. You had to cross the foaming Zanskar on a makeshift, hand-pulled trolley to reach Markha. It’s an untouched part of the world, frequented mostly by foreign trekkers. I did not encounter any Indian traveller during the five days that I spent walking through the valley. It is a treasure house of plant fossils, and I returned with a bag full of ‘stones’ that looked like dried pieces of trees. Nights were spent in the hut of the village headman who usually opened his carpeted living room for tired trekkers. Some evenings the locals danced and chhang (a locally brewed toddy) was passed around.

What’s next for Chander Suta?

A third book is in the pipeline and there are plans to restructure my farm. As for the adventure – it’s the fuel that keeps me going.

How would you like to be remembered?

I am an ordinary woman who tries to make the most of whatever place or situation I find myself in. I love to explore people, places and things. Will be happy to be remembered for all the fun things I did with my friends and colleagues.

Finally, how do you like your coffee?

Strong and freshly brewed, with a dash of milk.

Buy the books here –

Missing in Action: The Prisoners Who Never Came Back : Dogra, Chander Suta: Amazon.in: Books

Manoj and Babli: A Hate Story eBook : Dogra, Chander Suta: Amazon.in: Kindle Store

Ordinary Woman !? I completely disagree ! The rest is her humility !

A woman who dons many hats and adept at all .

Most inspiring to be so persistent at the kind of determination that is needed to write a book like this .

Thank you for the read, and always for your wonderful feedback Bela. Agree, Chander Suta’s persistence and determination is hugely inspiring.

Agree with you Ashish, Chander Suta is an extraordinary woman, and yet so humble.

Good read. Great lady to achieve so much in such different fields is highly commendable. Amazing spirit she has. Guess her family being her biggest supporters helped her turn her dreams into reality. Way to go Ma’am. Keep soaring.

Ultimately it’s only the loved ones who remember…..very

well researched Rashmi.Definitely not ordinary….

Wow! Respects….to a great writer, agriculturist, trekker..and so much more. Chander Suta’s dogged determination to give it her all is more than evident, be it through her writings, through her farmer’s heart or through her extreme connect with nature.

Yess, and kudos to you Rashmi to adeptly bring it to the fore and with a wave of panache…