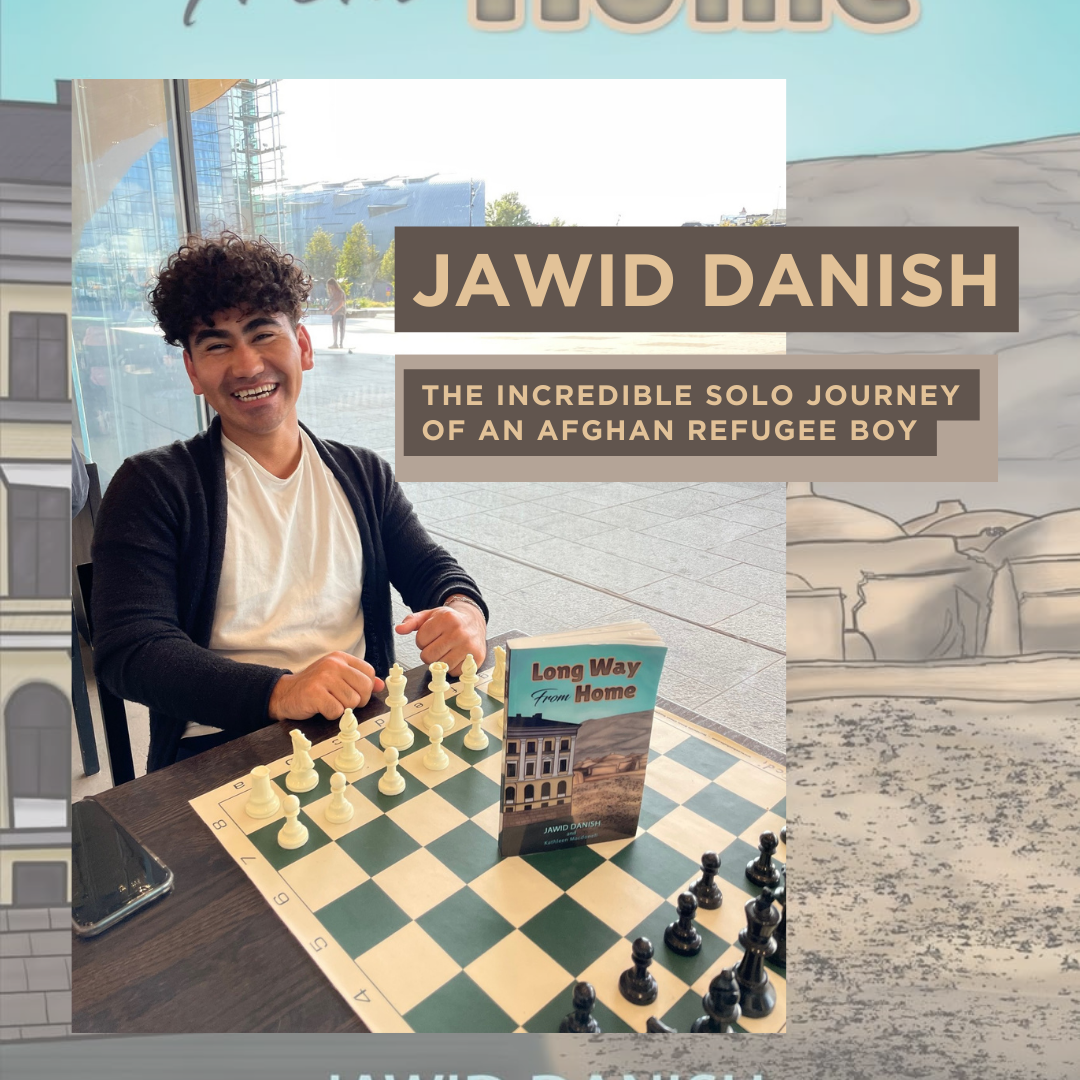

Jawid Danish and I sit across from each other at the Oodi Library in Helsinki, Finland, a community space in a country that prides itself on equity and equality. There are several chess tables set up for the public and we are in the midst of a game. “If you put your knight there, I’ll have your king in two moves,” Jawid says gently. He peers at me with his dark eyes. He is distinctively Hazara looking, with prominent East Asian features and thick black hair. And his smile is wide and genuine. I laugh out loud, embarrassed at my lack of chess knowledge but thankful for the lesson. I already know that Jawid is a skilled player – he runs the after-school chess club at my children’s school, where he is also a recent graduate.

I first became aware of Jawid and his remarkable story last year when a fellow parent and I bumped into him in town. She chatted with him briefly and afterwards said, “He is such an amazing young man. His story is incredible.” She told me he was a refugee from Afghanistan and came to Finland as an unaccompanied minor when he was just twelve years old. It’s hard for me to reconcile someone the same age as my football-and-Fortnite-loving son could have made such a challenging journey, let alone by himself.

Last spring, he published his memoir, entitled Long Way From Home. For the book launch, he gave a presentation to school parents and started by showing us a photograph of a rubber dinghy, ones we often see in newspapers with tragic headlines. “This is the same kind of boat on which I crossed from Turkey to Greece.” He described his childhood as an orphan looked after by his older brothers and what early life was like in the rural village that was home. He spoke about being Hazara, a minority Muslim group marginalized and often brutalized by the Pashtun-led Taliban, the loss of his family, and his need to leave his beloved country alone at the age of twelve if he were to survive. He detailed his treacherous journey through three countries led by people smugglers, some with humanity, and most without, to arrive in Europe, finally safe, only to be treated without dignity by those he thought would help him. He also spoke about the contrast between his life just a few years ago – tussling with other students for a spot on the rug on the mud floor of the classroom in rural Baghlan versus choosing a sofa for the bright and colourful classroom in Helsinki. And the resulting guilt he felt about having that choice. But not once did Jawid ask for our pity. And throughout the presentation, he remained poised, and even hopeful, as he spoke about his current university studies and work in refugee and human rights advocacy in Finland.

As a daughter of a Hungarian refugee who fled during the 1956 revolution, I was immediately drawn to Jawid’s story and wanted to root for him. Particularly as times have changed since my father was welcomed in Canada, and how the words ‘refugees and asylum seekers’ now conjure up populist fear-mongering headlines.

Jawid Danish’s book, Long Way From Home, is a raw and moving account of the chapter of his life dealing with the time just prior to leaving Afghanistan alone, including what prompted this danger-filled decision, to his arrival and settling in Finland, his new adopted home. It is co-written by Kathleen Macdonnell, an American teacher he met at the group home in Athens, who later became his guardian, and whom he calls Mom. The book started as his Grade 10 IB MYP personal project and it is one I highly recommend to those who wish an authentic and honest account about the arduous, dangerous, and traumatic journey thousands of people take every year.

Jawid and I move from the chess board to the upstairs terrace of the library, where we sit outside on a bright and crisp autumn day with our coffees. He has an air of ease and confidence, like most twenty-one-year-olds, but when he speaks, he carries himself with the wisdom and gravitas only earned through life experience.

We start chatting by about the journey that took him from Afghanistan to Iran, Turkey, Greece, and lastly to Finland, where he was able to be reunited with his brother via the refugee family reunification plan. His brother, Alijan, who is three years older, arrived in Finland as an unaccompanied minor on an even more treacherous journey a few years prior. Alijan is now a proud Finnish citizen and has just graduated from university as a nurse. When I ask him for details of Alijan’s journey, he says he doesn’t know specifics. “Afghans don’t talk about the past.” For Jawid, writing his book was cathartic and helped in his healing.

Of his own journey, I ask,“Were you scared of the uncertainty of the journey or was the risk of staying in Afghanistan greater?”

“I didn’t know the journey would be that difficult, and if I did, I probably would not have left. I would not take the same journey again. Living in fear, with no food or water for weeks.”

“Even though it would have been dangerous to stay?” I ask.

“I don’t think I would be alive right now if I would have stayed. I’m looking at my family and no one is left. All my remaining brothers are dead. But I couldn’t do that journey again.”

I ask about his older sister, who is married and remains in Afghanistan. “I try to talk to her, but it’s difficult. There’s a huge feeling of guilt. What am I going to talk about? Having a cappuccino, living in a beautiful city, going to university?”

“The book speaks about dignity, the loss of it, and what that does to a person. Talk a bit more about that.”

“For refugees, when you leave home, your only hope is to survive. When I got to Europe (Greece), I was put into something that was like a jail. Dirty and hopeless, in one room with 14-16 other boys. I would have preferred to die than be there. You are already damaged by crossing borders and mountains and deserts and rivers and getting beaten up by smugglers. Then you arrive in a democratic country, a first-world country, and they treat you like animals, worse than animals, and then all the hope you have is gone. Your dignity is destroyed totally, you’re not feeling like a human at all.”

We talk about his advocacy. Locally, he is involved with planning and giving speeches for refugee rights and participating in anti-racism protests. He also works with refugees to help them integrate into Finnish life, usually Afghans, but more recently Ukrainians. “The word refugee puts someone down. Negative things come to mind: runaway, dirty, needy, rapist, terrorist. Then the refugees themselves believe they don’t deserve anything. I try to help them aspire to be more than the labels society puts on them.”

He also helps refugees with confidence. “One refugee said that he works in construction because that’s the most he believed he could hope for. He couldn’t believe he would be capable of studying and accomplishing anything else.”

“You have had a lot of loss: your family, home, country. Yet, you remain positive. What keeps you going?”

“I always question myself. Remember who you are. Not long ago, you were a kid running cows up to the mountains in a small village in Afghanistan. I want to show people that even that kid can be someone. Of course, I want to have a good future. I want to help people and spread positivity and I if could, I would make the world safer so no one would have to take the same journey I took.”

“Tell me about your plans for the future.”

“I don’t know what I’m going to do for the future. I’m trying to figure it out. At the moment, I’m just trying to keep myself busy, going to university and expanding my network for business and advocacy. I’m hoping to go to Germany to study next year as part of a double-degree program in business studies, so I need to work and save money for that.”

“You’re a very good speaker – emotive and articulate. Have you thought about politics?

“I am thinking about politics. After I finish my bachelor’s degree, I’d like to continue higher education in the field of diplomacy, and maybe study international relations. But sometimes, I’m not exactly sure what I want to do with my life.”

In some small ways, Jawid appears to be a regular twenty-one year-old – he likes hanging with friends and playing sports. But then you take in the whole picture – his background, his passion, his vision, and you know he’s anything but regular. I have no doubt that Jawid Danish, a bright, intelligent, and talented young man will find his calling, and that he will effect positive change in the world.

Christina Matula

Christina Matula is a Canadian of mixed Taiwanese and Hungarian heritage. She is the author of the middle-grade books set in Hong Kong, The Not-So-Uniform Life of Holly-Mei, and The Not-So-Perfect Plan, as well as the picture book, The Shadow in the Moon. She now lives in Helsinki, Finland and is attempting to learn chess.

Jawid’s refugee story is both heart-breaking and inspiring. It is hard to imagine how he found the courage and resilience to survive, and yet he did. A beautiful write-up Christina. Like you, I believe Jawid will make a big, positive impact on this world.

Inspiring story, thank you for sharing and bringing his struggle to light, Wishing Jawid all the very best in his future endeavours, am sure he will be a shining light for humanity