Oneness to Cohabitation: A Wiccan Perspective

There was this afternoon in late autumn at a beautifully serene place called Guijan, near Tinsukia at Assam, in the Northeast of India. Now, there are positives and negatives to being in the eastern fringe of the country — it’s morning very early, it’s evening very early, and it’s dark very early, too. We had just gone through the rigours of a poetry festival at Ledo, and all of us wanted to laze around for a day before we headed off to our respective homes. The boat ride on the Guijan River, with the other side being the Dibru-Saikhowa National Park, and a wish to spot some Gangetic dolphins, began with a lot of excitement. After some time, as it slowly started getting dark, there was pin-drop silence in the boat. The motor was screaming alone; the sky was then a palette of blue, yellow, and grey, and the canvas on the horizon looked like an alligator with an open mouth. I stood at the deck, my arms and legs had practically given up — then, there was an iron structure on the bank… It took me no time to understand that this is the place where the dead are cremated. I took my camera and pressed the shutter halfway down; I could see a shadow moving around. The incorrigible Wiccan in me refuses to take rest. I named this unison as Cohabitation. Never did I know then that a book shaped like that bygone compact disc cover would justify this. Oneness is nothing but the poet’s way of cohabiting with the eternal, ethereal and terrestrial.

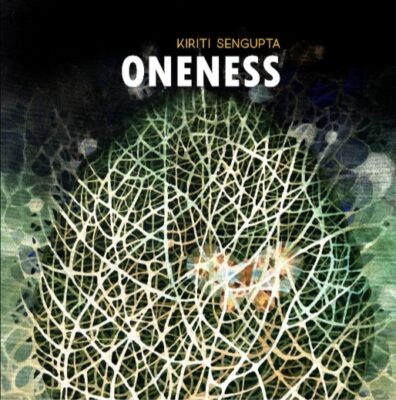

Oneness is not merely a book; it’s a collectable. It has about twenty poems and an equal number of paintings. The book starts off with a frontispiece and then delves into some very deep poetic nuance. It has 53 pages, and the cover design by Bitan Chakraborty has adopted the 1978 painting of Samir Mondal, Impediment.

Kiriti Sengupta is a well-known name in Indian English poetry circle with many feathers adorning his cap. His poems are known for their deep and covert spiritual leanings, expressed in terse words, leaving the reader, with a mouthful lines to chew and digest with time. As far as Pintu Biswas is concerned, this is my first exposure to his work.

As a Wiccan, my insights into such a pocket-sized work become very intense. I find the Wiccan philosophy embedded deeply into each and every nook and corner of this book. My teacher, the High Priestess of the Wiccan order, Ipsita Roy Chakraverti, says that everything in this world is animate and that the word inanimate is a misnomer. She gives it away to the sceptics, forgiving them for their obstinate and ignorant blindness. She goes on to the extent that everything on earth has consciousness of its own — it thinks, it feels, it delivers, and then it survives.

From my Wiccan eyes, I also see Oneness as a conscious piece of work that emotes, speaks, and smiles yet is helpless and ecstatic and bears a mind, a body, and a soul. From where I see it, I find a portal—a Wiccan portal that helps to transport us through myriad dimensions. The mind and the portal, in this case, mingle to form a conscious opening, implying in no uncertain terms what’s inside.

The cover and the title Oneness form the mind of this book. The mesh on the cover looks at me and smiles as if to alert me of the depth of mysticism that lies ahead. I cut through the weeds, into the dark background and then through the praises and the verso and the contents, and then, I am thrown aback with the mightiest of poetic strength:

I rived my eyes

for inditing poems.

Would you reckon them

by their length?

This frontispiece closes your nostrils and forces you to hold your breath. Your moist eyes would love a life, these lines will not let you die. The portal is now open. The mind is breathing, and the mists are slowly clearing. The potent fourth dimension is now active, and the proof of animation is slowly holding its ground. The dimensions are now open for the body and the soul to drown in their own consciousness, to live on their own, and most importantly, to make their presence felt.

The body of this book definitely consists of the colours that make up the physical manifestations of Oneness. Wicca had been smitten by the colours and strokes (of nature and otherwise) for times immemorial, and the artist Pintu Biswas, somehow, has catered to exactly how a Wiccan looks into things. The paintings use bold and, at times, nonchalant colours, and the confidence with which the artist gallops between the abstract and the truth is something that the beholders (or the readers) would be in extreme awe of. I have reasons to believe that neither the poems are ekphrastic nor the paintings are completely inspired by the poems — a loose sniff through the book might seem otherwise. The striking painting of a crow (page 22) against the haiku on the opposite page has semblance but no resemblance. The body is not always the manifestation that is visible. It is, on most occasions, the one that exists beyond it. Another painting that really caught my eye was on page 36, where, perhaps, the artist speaks of a path to eternity. The pattern is unique as the strokes deny any sort of regimentation. The beauty lies in the indiscipline. Then there is the painting of a Buddha bust and, of course, (how can I miss it) on page 28, the covered man in white flaunting a dark background. The paintings in this book need separate attention. They are a complete diet in themselves, with lumps of vitamins, minerals, and carbs, but if they live in this book, it’s because of the existent soul in them. And the soul is nothing but Sengupta’s poems.

The frontispiece was just a trailer, or as I mentioned earlier, a part of the portal that led to this extraordinarily nuanced collection of poems. The haiku section appetizes the readers, like the first dip that a child has in a swimming pool — the sounds of bubbles, the blank look, and the unknown feeling of claustrophobia. Goddess Isis, the moon Goddess, who adorns my altar, perhaps forced me to take a look at this haiku:

full moon

across the landscape

fireflies

This reminds me of the place I was born in. When Isis smiles in her silver glitters over the tea gardens of Bogapani, the fireflies burning in unison form a myriad canvas of impeccable poignancy. And then, again, with a bit of sarcasm and a wholesome serving of satire, this haiku changes the direction from ethereal to pragmatism:

plagiarism

the author examines

the reader’s memory

I feel like giving an impish grin reading this, a naughty wink, but as a non-academic, I have to understand how the privileged classes behave—I must follow suit. Then, out of nowhere, a prose poem pops out. Sengupta is known for his approach to poetry—terse and high-impact verses. But a prose poem titled “Is Winter Back in Delhi?” is a pleasant inclusion, to say the least.

“Will this abrupt climate change make me indulge in the luxuries I cherished in the past few months?”

With a person wrapped in colours on the facing page, this poem looks at the change in climate with a pinch of saltless spices. And then there are poems such as “Antara Marwah Walks the Ramp” (page 27) or “Primordial Leaning” (page 31) that hit us with lines like:

“…when you

imply the goddess, do you illustrate

sisterhood with many limbs? Would you

like men to act as Shiva — the destroyer?”

These are just a few pinches of the poetic shock, but the most intriguing is a poem written in a series entitled “On Exit.” It has four verses —impactful, and all of them have Sengupta written over their face:

“Does grief know

its future?”

The series, dedicated to the poet’s father, starts off with these lines. However, the depth it reaches with Kiriti Sengupta’s use of lucid language is the most phenomenal feat. This is, in fact, true for all his poems in this book — easy to read, yet breathless to fathom. “On Exit” ends with:

“…I realized

my father’s passage from

his bedroom to the crematory

was therapeutic.”

It is believed that the virginity of an experience should not be taken away by knowledge, so I won’t divulge more about the book. To conclude, I would like to add that Oneness in itself is a scrumptious meal that needs to be munched, ruminated and then gulped. The mind, body and soul of Oneness are not complementary per se; they exist separately with the finest of ectoplasmic beings. Oneness is cohabitation — not a peaceful state of being but where one pushes the other to excel. A huge shout out to Transcendental Zero Press for being this colourful connector between the artist, the poet and the readers. Oneness mingles with the shadows of the terrestrial.

Rajorshi Patranabis

Rajorshi Patranabis is a multilingual poet, editor, translator and reviewer dabbling into different forms of poetry.He has this knack of writing in fewer words with a lot for the readers to ponder about.A Wiccan by philosophy, he has ten collections of poetry( nine in English and one in Bengali) and four collections of translations ( two co authored with Dr Ranjit Dutta of Assam).

He has collections of sonnets, haibun, haiku, ghazals and free verses. He is credited for the first ever collection of Gogyoka titled The Last drop of your Tears, published by Hawakkal prokashona and launched at World Book Fair, 2023, New Delhi, which had been translated to Assamese and is currently being translated to hindi. He is also credited with the first ever collection of Gogyoshi titled Checklist Anomaly by a single author in English, also published by Hawakal publication.His last published collection is Soliloquy (Ghazals in English ) from Penprints publication. He has been awarded the Rashtriya Samannay Samman by Kavyadhoni Assam.