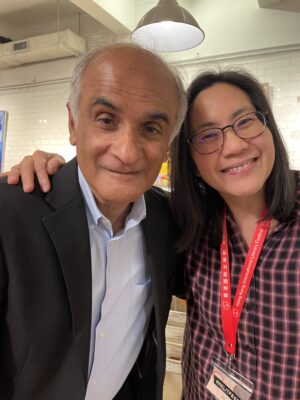

I’ve admired Pico Iyer’s writing long before I had the honour of being in conversation with him at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival in 2023. A brilliant essayist and keen observer of life, Pico has authored over 15 books, including The Global Soul, Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk, The Half Known Life, and most recently, Aflame: Learning from Silence. Pico kindly offered his thoughts on some of my questions about his latest work.

Pico, congratulations on the release of Aflame! It feels like no time has elapsed since we last met in Hong Kong in 2023 to talk about your previous book, The Half Known Life, but since then, the world has moved on in largely tumultuous and troubling ways. How have you managed to stay so focused and so prolific in these discordant times?

I think writing is my response to discordant times, my attempt to bring calm and clarity in the midst of the tumult to myself and to any reader who wishes to accompany me, and I almost think it’s the writer’s job not to write to the times, but against them, by opening up a larger space in which the dramas of right now can be set so they find their right proportions.

Every morning, in the pre-dawn dark, after a simple breakfast of toast and tea, I walk a few steps to my tiny desk, and it feels as if I am stepping into a cabin in the woods. It’s a form of meditation, perhaps, and certainly of sustained contemplation, and it’s only by stepping away from the world for those first five hours that I can gather my thoughts and resources, make sense of all that I feel and have experienced and prepare myself for the onslaught to come.

To me, it hardly matters what comes—or doesn’t come—out of those hours of quiet; it’s simply a chance to step back so as to catch the larger picture, try to see the proportions of the world and to remember what I love.

I worry that certain leaders, and the media for which I have long worked, try to keep us in a permanent state of distraction, agitation and high emotion—even though, arguably, no more is happening in the world than has ever happened. So our task, as individuals, is not to be taken in by the ruse and not let the moment obscure the years or even eternity.

I remember how every morning during the pandemic, I woke up and faced what looked to be a clear-cut choice: would I attend to what would cut me up or to what would open me up? Would I listen to the news and feel powerless and despairing as I read of bodies piling up in Iran or overcrowded morgues in Bolivia or grandstanding heads of state—tragedies all, but ones that I could in no way affect? Or would I look out the window at the bright April sunshine and take a walk and feel flooded with light and hope and possibility?

Years ago, William James reminded us that our lives are defined simply by what we choose to attend to. I prefer to look to what sustains, what deepens and what uplifts than to what cuts us in two that I can in no way remedy or affect.

Aflame feels like a departure from your prior books, which centred on your escapades in far-flung, often misunderstood lands. In this book, your eye has turned inward, looking for something hidden in the familiar, in your regular visits to the New Camaldoni Hermitage in Big Sur, California. Even the five sections of the book seem to conceal some sort of hidden code, and the prose, while written in your customary luminous style, is delivered in short vignettes, inviting us to guess who you’re alluding to, where you are in place and time, which book you are reading. What is the thinking behind the structure and purpose of Aflame, and how do you hope readers will approach Pico Iyer’s latest offering?

Thank you for such a thoughtful and sensitive reading. I did work terribly hard, over years, to try to give my book a narrative arc, over those five movements, to offer the reader an unfolding story to follow and to confer a sense of forward motion, as I travel from solitude into community, from uplift into reality and from ignorance towards qualified knowledge. As the wonderful title of the Jack Kornfield book has it, “After the ecstasy, the laundry.” Ecstasy is only as useful as the extent to which it helps us cope with the laundry and all the daily stuff of life.

At the same time, just as you say, I was working to make each passage a self-sufficient parable of sorts, which could stand on its own as a koan or opening out of time. And I wanted to make the pacing very human—slow, deliberate, precise—to offer the poor reader a release from the rush and distraction of the world.

So my hope was that I could give the reader who wanted a story, but I could also fashion a book of allegories that you could open at any place and read for three to five minutes and that would leave you both calmer and closer to your deeper, too often forgotten self.

Part of the challenge—and the delight—of the book was taking 4000 pages of notes, gathered over 33 years (or half a lifetime), and turning them into something as short, charged and suggestive as a haiku. So, I wanted the silence between the passages to speak and the white space around the words to offer an invitation for the reader to complete, as in a classic pen-and-ink painting.

The Greeks famously speak of two kinds of time: chronos, the time marked by the calendar, and kairos, the moments when we step out of the clock and taste eternity. Those moments when we feel released from ourselves and attuned to something beyond us—”peak moments,” as the growth psychologists call them.

In the monastery I describe, there’s actually a trailer where sometimes I stay called kairos, or sacred time. And so, although I’m telling a story that develops over 33 years, I most of all want to take the reader to those out-of-time moments that bring him/her back to their truest self, that farther reality we sometimes overlook, what T.S. Eliot called “the life we have lost in living.”

The content of this book feels much too familiar; my wife calls me a “stuck record” because I keep saying and writing the same thing, decade after decade. I first wrote about the hermitage and silence for Time magazine in January 1993, the week of Bill Clinton’s first inauguration (when my editors knew the world would be too noisy). When National Geographic magazine invited me to go anywhere in the world, on their dime, for as long as I wished, to write about “a special place,” back in 1996, I wrote only about Big Sur and the hermitage. When the New York Times magazine put together an end-of-millennium issue on adventure in 1998, the only excitement I could think of to describe was that of going on a retreat to this monastery.

But although I’ve been tilling the same ground for all these thirty years or more, the fun was to try to come up with a very different structure, so every passage that remained (of the 3800 pages I cut) might act as a small explosion and could be appreciated out of context as a message from the world outside of time.

I worry that we’re losing what is most precious in us, our secret treasure-chest, and I feel my job is to try to help us recover that, both through my words and through my silences, the space around those words.

Your first visit to the hermitage was over three decades ago, after you lost your home to wildfires, and you’ve been drawn back to the hermitage regularly since then. Is there a pattern to your visits, and do you have any suggestions for how readers who don’t have access to similar hermitages can create a sanctuary for themselves? How do you balance the responsibilities to your soul with your responsibilities to your loved ones?

That’s a perfect question, and I have come to feel that I can only bring something creative and fresh and joyful to my loved ones by stepping away from them at times to gather my resources; otherwise they’re getting nothing but my distraction, my exhaustion, the sight of my disappearing back as I mumble, “catch you later!”

On almost every trip I take to the hermitage, I feel really guilty to be leaving my aging mother behind. Worried that my bosses can’t reach me for 72 hours since there’s no cell phone or internet reception there. Frustrated that I’m missing a friend’s birthday party.

But as soon as I arrive in the silence, I’m reminded that it’s only by being there that I can come to life again, recall what I owe to my loved ones (as I can’t always do when racing from supermarket to bank to pharmacy) and collect the light and hope that are the best gifts I can possibly share with them.

All of them, of course, can survive quite happily without me for 72 hours, and when my mother sees her only son at the front door alight with excitement and attention and delight, tumbling over to share fresh excitements with her, she’s thrilled. Too much of the time, when I’m with my loved ones, I’m not really with them because I’m too caught up in what I have to do six minutes from now; it’s only by recalling what I should be doing six months from now that I can come back to earth, as it were, and be fully present to them.

I’m keenly aware that many people don’t have the time or resources to go on retreat as I do; they have all-consuming jobs, small children, or aging parents who need them every moment. But they can bring most to all of those, I believe, if they can find the courage to take a long walk by themselves to clear their head–or visit a friend without a cell-phone, or just sit quietly in one corner of the house, without devices, to gather the clarity and attention they need to bring to others.

I notice that, too often, I’m killing time while waiting for my wife to come back from her job, say. So one day I decided to try to restore time instead—by not turning on the TV, not scrolling idly around the internet and by just turning out the lights and listening to some music. I was astonished how that home-made, 40-minute retreat made me so much fresher when I heard her key in the door, allowed me to sleep so much better, helped me awaken much less frazzled. The more we feel we don’t have time to take a break, the more we’re clearly in urgent need of a break.

Fire features often in Aflame (even the title!), and you often allude to the loss of your home and the close shaves you and your mother had many years ago in wildfires. Yet, you continue to visit the hermitage – a sort of second home? – despite the chance of it being swept away by similar fires. Pico, do you think there is a reason you deliberately put yourself in the position of possibly reliving the fear, a little bit like how you take night walks despite possibly being made a meal of by a mountain lion?

I think fear exists largely in the mind, and I can only get over it by going through it, as it were. Many people ask me if i’m not scared to spend my time in Iran and North Korea and war-zones from Beirut to San Salvador, and I recall that the scariest moment in my life came right next to my home in affluent, protected, all but gated Santa Barbara, when I was caught in the midst of a devouring fire for three hours.

Places are only scary if you don’t know them, and you relieve the fear only by taking yourself to the West Bank or Yemen or South Africa or wherever it happens to be and confronting the human reality that the news too often neglects. And, of course, wherever I go, people point out to me that the really frightening places, from their point of view, are Los Angeles and New York.

You’re absolutely right that my family, like the monks, know we’re living where humans were probably never meant to live, and we’re trespassers of a kind; it’s not the mountain lion that is intruding on our territory so much as we who are intruding on hers.

We also know that the pine trees, meadows, and manzanita that are intrinsic to the beauty of the California landscape can’t survive without fire. Fire is nature’s replenishing agent, its Easter force that enables regrowth and fresh life.

So, if we can’t live without fire, we have to learn to live with it. Fire here, of course, is a metaphor as well as a literal threat; as during the pandemic, all of us, in our different ways, are having to think about how we can live calmly in the face of mounting uncertainty and how we can sustain hope in the midst of impermanence.

Jung famously wrote that the difference between a good life and a bad life is how we walk through the fire, how we negotiate the challenges and the losses that are part of any life.

At the same time, the most cited sentence in the bible is “be not afeared.” And my monk-friends, even as they’re encircled by flames that threaten to take away their lives and to take down everything they love, calmly continue going about their offices and sign off in the middle of an evacuation, while many are fleeing for their lives, “blessed day all.”

The sad truth is that fires are not going to go away by my pretending they’re not a force of nature (or what my monk-friends would call an “act of god”). So let me face up to them and see how they’re something deeper and more complex than my simple ideas of “threat” or “devastation.”

Pico, you explore death often in your book, from good friends lost to illness to the demise of a disoriented wasp. Do you feel that your retreats into silence are helpful, even necessary, perhaps, as you grapple with your own mortality?

Beautiful; the essential question. And yes, I think coming upon something that doesn’t seem quite so fragile and short-lived as we are—whether it is the ocean, the great cliffs of Big Sur, the centuries-old redwoods all around, or a 1,000-year-old monastic practice of prayer and service—makes impermanence a little less scary.

When my father died, quite suddenly, at the age of 65, and I had to work round the clock to protect my mother and take care of condolence calls, the obituary, the memorial service, the best way I could come to terms with the loss was by taking myself, for two hours, to a bench above the sea and grounding myself in everything that doesn’t change so often: the Pacific Ocean all around, the cloudless blue sky, the wind moving through the pampas grass, the bells in the distance.

I took great care to place a lot of death in the book, a reality we can’t dodge, and I worked to include a lot of joy. Because the challenge before most of us is how to sustain joy even in the face of mortality, how—as the Buddhists say—to participate joyfully in a world of sorrows.

When I first went to stay with the monks, I was simply trying to learn how to live. The longer I stayed with them, the more I realized I was learning how to love. And then I came to see that at some level, as among all monastics, I was learning how to die—and, even harder, how to be with those one loves as they die.

My central question of myself is, what do I have to bring to the I.C.U.? Given that I and most of the people I love are likely to find ourselves in an intensive care unit at some point, what do I have that can sustain them and support myself?

For me, it’s only the time in silence that I’ve spent that really fills my inner savings account and ensures that I have resources within to bring to life’s difficult moments.

We prepare so much for driving tests, job interviews, or even first dates. But sometimes we neglect preparing for the one thing that’s a certainty in life: its end. I wouldn’t want death to catch me completely unaware, if possible.

Pico, at one point in your book, your mother asked, with some concern, if you’d convert, and you assured her you would not. Yet, as evidenced by your writing, you are very spiritual and have a deep and profound respect for many religions. Is there a reason why you’ve eschewed organised religion and continue to do so?

All the reasons are bad ones, I fear. Yet, I think what I believe is less important than how I act. I have friends who share my assumptions and who act in ways that horrify me, and I have other friends, like the Benedictine monks I honor here, who live by values different from my own but who humble and silence me with their compassion and devotion.

I also, as in my last book, feel that it’s words and beliefs that are cutting the world into two and creating a more divided planet and set of nations than I’ve ever seen, even as silence and our common humanity exist in a place beyond all that.

Someone falls to the ground on a busy Hong Kong street, and we reach out to help her up, not caring if she’s Islamic or Christian or nothing at all, whether she voted for this leader or that one. But beliefs too often move us to assume we’re in the right, which means most other people are in the wrong; it cuts us up into “us” and “them.”

I’ve always appreciated the Dalai Lama saying that religion is a wonderful luxury that can add savor to life, like tea, but the water that we can’t live without is everyday kindness and responsibility.

I’d rather concentrate on that than on the texts or words I might place upon that kindness.

The central theme of Aflame is what lessons one can take from the silence and solitude of retreating into a hermitage for a period of time, yet it is your interactions with other human beings, other seekers of solace or comfort or themselves, that seem to teach you, and us as readers, equally, if not more valuable, life lessons. So, while there is a need for humans to be comfortable with solitude and to be able to endure some degree of monasticism, ultimately, we need to be with each other and to care for each other. Do you feel this is increasingly under threat in recent times, and if so, what can we do about it?

We’re all aware that we’re living in ever more disconnected ways and that the technology that unites us on the surface often divides us deep down. We’re all painfully conscious that we define “connection” more and more in terms of phones and planes and less and less in terms of basic human relations. After studying the effect of digital life on individuals and families for forty years, the psychologist at MIT, Sherry Turkle, notes that if you don’t know how to be alone, you’ll always be lonely, just as the Trappist monk Thomas Merton noted seventy or more years ago.

You’re absolutely right that this is a book about community and compassion, about drawing closer to others in an age when intimacy and attention are often luxuries we feel we can’t afford as we race from one thing to the next, multi-tasking every step of the way.

But for me at least—and this is the point of the book, as you say—I could only realize the importance of community by traveling into solitude. It was when I was alone in my little monastic cell that I could best remember the ones I love and my obligations towards them. It was when I was quiet that I had most to share in conversation. Indeed, it was only by sitting alone in silence in the monastery that I saw the necessity of getting married and could find the courage to do so!

My worry is that when we’re racing through our overcrowded lives, with the world speeding up to a post-human pace, we’re not really in a position to recall what’s most essential or to sift what’s trifling from what’s important. We’re ever more captive to the moment—to what CNN is broadcasting right now or to that text we received six seconds ago.

So we lose all perspective and proportion, and as the flames race towards us—or the waves of a tsunami or the winds of a hurricane—we can’t put our hands (or minds) on what is really vital.

I have only been able to see what I owe to others and cherish it by stepping away from the rush (sometimes even from those others) for a moment. We live in a two-room apartment we formerly shared with our two kids. There was so much going on and so much noise and movement that often we couldn’t hear ourselves think, couldn’t hear ourselves not think, couldn’t give our full attention to one another and certainly couldn’t recall what was really important for everyone around us.

If you’re standing two centimeters away from the world, I’m not sure you’re in a position to make sense of it—or to see what really matters.

Even as you’re fanning the flames of your new book, I’m sure you have another project lined up. What can we expect from you next, Pico?

I’m just completing my next book, which is about the final seasons in my mother’s life, woven around four plays by Shakespeare.

Shakespeare has been my friend ever since I first appeared in one of his plays at the age of five, and then began teaching his work in my early twenties while studying nothing but literature for eight years. And, of course, he was one of the things that I shared most with my parents, good products of British India as they were.

As I tried to nurse my mother through her eighties—by her side for months on end as her only living relative—I found the only self-help book and counselor that was of any use was King Lear. Everything about the predicament of aging, the challenge of caring for elders you can no longer recognize (or who can no longer recognize you), the sorrow of dementia and the heart of familial love is in those pages.

And of course, even beyond outlining the seven ages of man, Shakespeare’s work traces the shape of many a life, from the frothy early romances through the midlife anguish and even hopelessness of the problem plays and tragedies to the autumnal restorations and seasoned, ripened hopefulness of the final plays.

As the world seems to grow more tumultuous and noisy, to go back to your first question, I want to stay with counselors who can offer me clarity and wisdom in the midst of the clamor. Whether it’s my mother, my Benedictine monk friends or Shakespeare, I rejoice and am humbled by all they teach me about compassion and wisdom and the bringing of the two together. The more the world speeds up, the more I’m grateful for something that can take me back to the heart of humanity.

So writing of Shakespeare is my private indulgence that I hope to share with—maybe I should say “inflict upon”—any reader who’s interested!

Pico Iyer

Pico Iyer was born in Oxford, England in 1957. He won a King’s Scholarship to Eton and then a Demyship to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was awarded a Congratulatory Double First with the highest marks of any English Literature student in the university. In 1980 he became a Teaching Fellow at Harvard, where he received a second Master’s degree, and in subsequent years he has received an honorary doctorate in Humane Letters.

Since 1982 Pico Iyer has been a full-time writer, publishing 15 books, translated into 23 languages, on subjects ranging from the Dalai Lama to globalism, from the Cuban Revolution to Islamic mysticism. He has also written the introductions to more than 70 other books, as well as liner and program notes, a screenplay for Miramax and a libretto. At the same time he has been writing up to 100 articles a year for Time, The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the Financial Times and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. His four talks for TED have received more than 10 million views so far.

Maureen Tai

Maureen Tai is an award-winning Malaysian writer living in Hong Kong who has published creative works in literary and online magazines such as Cha, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Kyoto Journal, Mekong Review, Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, Coffee and Conversations, Porch Lit Magazine and the Hooghly Review, as well as in local and international anthologies. Primarily writing for children and teens, she has published short stories for children with Oxford University Press and Marshall Cavendish (Asia). Maureen’s work and book reviews can be found at www.maureentai.com. She counts her time as the Program Director of the Hong Kong International Literary Festival in 2023 as a highlight of her literary career to date.