People often cite interpreters as the group of Afghans most vulnerable to Taliban reprisal in Afghanistan. However, Afghans who have worked for nonprofit organizations are also in danger, and many are desperate to flee the country.

One such person, I’ll call Farhad. I reached out to him after I learned that the Taliban had taken Herat. Farhad told me that he is terrified of what the Taliban will do to him and his family and wants to find a way to immigrate to the United States. He said he hopes the world will not forget about the Afghan people.

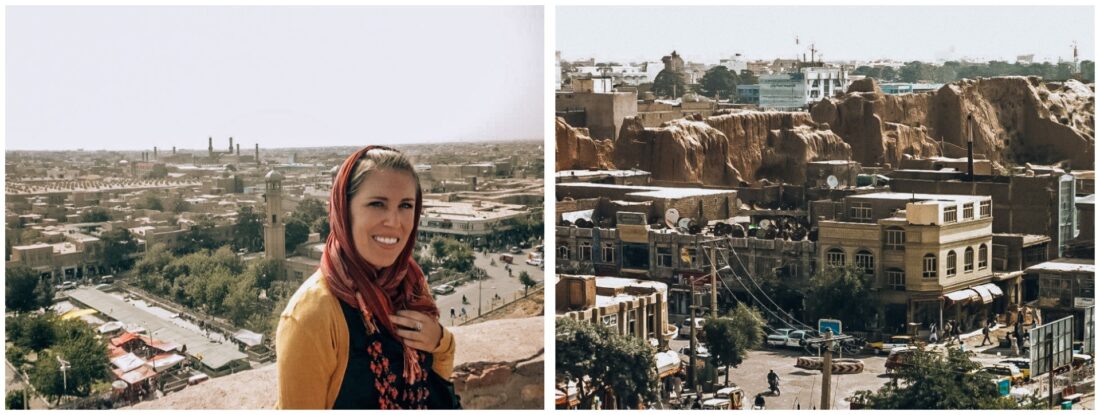

I first met Farhad when he picked me up from the Herat airport in 2012. I was moving there to start a job with an American nonprofit.

“Nice to meet you, Emilie-jan,” said Farhad. Using “jan” after someone’s name is a token of respect and affection in Dari, one of Afghanistan’s languages. Throughout my time in Herat, Farhad was always warm and smiling. I sensed he wanted to bridge our cultural divide by treating me like a friend.

My expat colleagues at the nonprofit felt similarly about Farhad. He was our driver during the week, ready each morning to take us anywhere we needed to go. Farhad was always kind, always asking us how we were and if we’d spoken to our families back home. For the Eid holiday, he invited a few expats to his house to celebrate. He made us feel comfortable and welcome, and we all trusted him completely.

Fifty years old and born in Herat, Farhad is married with five daughters and two sons. He works hard and, for fun, plays volleyball. He is not so different from most people I know, except that he had the misfortune of being born in a country at war since 1979.

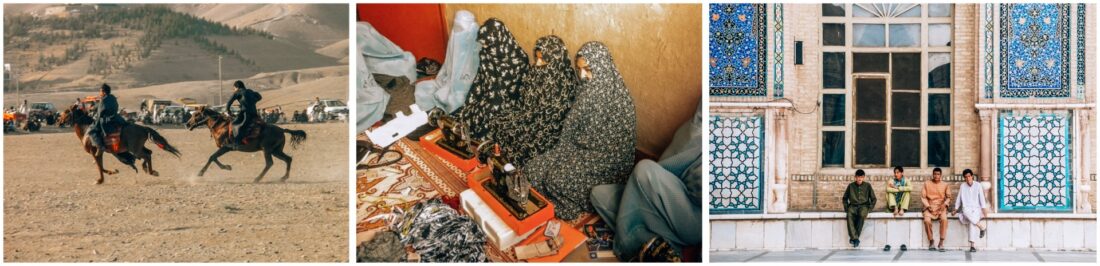

When the Taliban invaded, Farhad and his family were at home, hiding. They could hear shooting and explosions from rocket-propelled grenade launchers (RPGs). Businesses closed their doors, and for the next few days, people stayed home. Farhad tells me that Herat is still quiet. Women and girls remain indoors because the Taliban have announced that they should not be in public places, such as work or school, mixing with men.

With the Taliban in power, Farhad is afraid for his life for one main reason: he believes they will punish him for working for the Americans. The Taliban have launched countless attacks on foreign organizations and businesses over the years, including an attack on a Turkish company that left Farhad’s brother dead. Farhad is not wrong in worrying he might be next.

Farhad is also anxious about what will happen to his wife and daughters. His eldest daughter recently graduated from high school and was looking forward to attending university. Now, this doesn’t seem possible. Farhad explained that under Taliban rule from 1996-2001, women were whipped for leaving the house without a burqa or a male escort and were forbidden from working. He thinks they may implement these policies again.

Despite the Taliban’s attempts to reassure the world that they’ve softened, Farhad tells me that he does not believe they’ve changed. His daughters grew up in an Afghanistan where women had access to education and were free to work. In this Afghanistan of the past twenty years, the Taliban repeatedly demonstrated their aversion to women’s empowerment, launching numerous attacks on aid workers and activists for their role in promoting Western culture and the mixing of the sexes. It is naïve to think they have changed their values overnight.

When I ask Farhad about the future of his country, he tells me, “I have no hope for Afghanistan. It is now back where it was twenty years ago.”

With the Taliban in control, Farhad wants to get his family out—to the U.S., specifically. “The U.S. is a great country,” he says. “Through my work, I’ve gotten to know its people and language. The future of my children will be good there and we will be safe.”

So how can Farhad become a refugee in the U.S.? Despite his nearly two decades of loyalty to an American NGO that trusted him with the lives of countless expat staff, he must get in line with the thousands of others who did not make it onto one of the evacuation flights.

He applied for a special visa program for those who have worked for American organizations, but hasn’t heard anything back. He is fearful of going to a neighboring country without employment or language skills. With the airport closed to commercial flights, rumors of border closures, and most of the banks shuttered and international money transfer services suspended, leaving Afghanistan seems to be a herculean task.

Even if Farhad makes it out of Afghanistan, the life of a refugee is not easy. After leaving Afghanistan, I volunteered with the Refugee Assistance Program in Washington, D.C. and was matched with an Iraqi family. They lived in a remote housing complex with other refugees, receiving a small stipend for the first few months. Because the husband didn’t speak much English, he’d been placed in a warehouse job processing flowers. The pesticides made him ill, and he decided to quit. His caseworker chastised him. A second chance would be difficult, and a third, unheard of. As I sat with them one afternoon, attempting to explain the contents of a letter from the daughter’s school that said she was failing, I wondered how the family would survive.

Despite being difficult, the life of a refugee receiving minimal support was preferable to life in Iraq. And I see that same dilemma as Farhad seeks to leave Afghanistan.

For many people like Farhad, life in a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan is far worse than life as a refugee. Not only do these Afghan refugees deserve assistance from our governments to escape lives full of fear and oppression, they deserve our compassion and understanding as they endeavor to create a brighter future for themselves and their families.

Share

Picture Credit : Emilie J. Greenhalgh

Great article Emilie, my heart goes out for all who were left behind. You are such a special person whom I care about an awful lot. You and all you are trying to help are in my thoughts and prayers.

Scott Bartlett

Really impressed by the words of this article, Emilie!! Also loved that you mentioned all the insights as it is like a raw experience so reading it was a satisfactory experience.

Thanks for it!

https://bloggingtogenerations.blogspot.com

Hope he and his daughter can reach America safely.