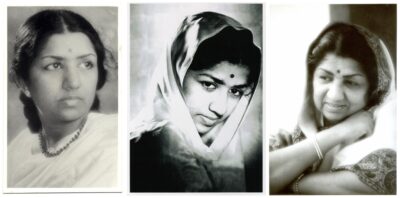

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of the first-ever recorded song of the legendary Lata Mangeshkar, whose songs are the soundtrack to three generations of South Asians. Volumes have been written on her artistry. Here, Jayang Jhaveri looks at the woman behind the formidable musical phenomenon, and how she blazed the trail for many female vocal talents in succeeding generations.

“It is eighty per cent God’s gift; the rest is effort,” declared the songstress during an interview when asked whether her ethereal vocal prowess was a result of hard work or something that had been bestowed upon her. While she may have unwittingly added fuel to the nature-versus-nurture debate that has forever been a staple of critics and commentators, there is little doubt that for Lata Mangeshkar, vocalist extraordinaire, staying at the top was most certainly hard work. Her talent and artistry were surely instrumental in her meteoric rise, but surviving and thriving in the male-dominated world of Hindi films was decidedly no cakewalk.

It all began eighty years ago after the untimely demise of her father when Lata, then a tender thirteen, was left as the sole breadwinner to shoulder the responsibility for four siblings, a widowed mother and an aunt. Many years later, she plaintively recalled how she had skipped adolescence for the uncharted waters of womanhood. Brought up as the eldest daughter of stage actor-singer Master Dinanath Mangeshkar, acting and singing were the only two vocations known to this child prodigy. For a while, Lata pressed both talents into service in the nascent Indian film industry to ensure survival for her family, which had seen glorious ups and penurious downs. She later settled for singing, which she had been groomed for by her classically trained father since she was four.

The world of 1940s celluloid was unabashedly male-dominated around the globe, and while newly independent India was no exception, entrenched patriarchy and social mores set it apart. Acting and singing were not considered respectable professions for ladies from “good” families; women entering films were deemed to belong to questionable backgrounds (many well-known singers and actresses were in fact daughters of reputed courtesans). Lata was thrust into this world unwittingly, and from an early age had to learn to navigate a male-centric milieu of producers, directors and composers. Her father’s enduring goodwill helped, but so did her quiet confidence in her art as well as her inborn self-respect.

It took barely a decade for Lata to establish herself as the go-to voice for leading ladies of the Hindi silver screen, who never sang their own songs. (Till date, “playback” singing – or lip-syncing to a recorded voice – is an enduring curiosity to Western observers.) Although her initial breaks may have been a result of happenstance, staying at the top required extraordinary talent and grit. Many early film music composers like Anil Biswas and Naushad found her vocal range a godsend, allowing them to push the musical envelope and give free reign to their creativity.

Over time, many members of the male league of music makers, perhaps fearful of Lata’s dominance, tried very hard to find alternatives and even to displace Lata and her younger sister Asha, who by the late-50s had also established herself as a force to be reckoned with. Try as some of them might, composers found it difficult to find a voice that suited heroines of that era and could almost guarantee hits, and therefore record sales, one of the only three revenue streams available in that era in addition to box office receipts and royalties from radio play. Thus began a series of whispering campaigns in the early 60s that painted the two sisters – and especially Lata – as domineering, conniving and manipulative women who could make or break a composer because of their untrammelled power. That they were beholden to a supremely talented woman was even more galling for these men, more so in an era where male dominance was the norm. Strangely enough, similar allegations have never been levelled at two of Lata’s male counterparts – the versatile Mohammed Rafi and the rumbunctious genius Kishore Kumar – both of whom ruled the roost from the 50s to the early 80s.

During one of my conversations with her, I asked Lata why she remained silent in the face of the “Mangeshkar monopoly” allegations. Pat came the reply: “Don’t you think I would rather devote that time and breath to vocal practice?”

It is telling when members of an almost entirely male industry protest loudly about a petite white sari-clad Marathi lady calling the shots. Drowned amid insinuations and thinly disguised barbs (gleefully amplified by pliant journalists) was the fact that nearly every producer wanted Lata’s voice for his film, and even composers who desired other voices had to comply – except for the redoubtable O. P. Nayyar, who famously swore never to work with Lata and chose sister Asha instead. Faced with a question from a scribe as to why he insisted on Lata, composer Madan Mohan replied with his trademark brusqueness: “Why me? Why not ask S. D. Burman, Roshan, Shankar Jaikishan and Hemant Kumar? We are all besotted with Lata!” He had named all the greats of that time – and even a stalwart such as S. D. Burman opted to patch up a minor misunderstanding that kept Lata away from his recordings for five years in the late 50s. To her credit, she has always promptly buried the hatchet with any composer gracious enough to offer an olive branch.

Professional to a fault, Lata is known to be a stickler for decorum and punctuality. Composers, however, dreaded the morning call where she gently excused herself from a recording when indisposed, because she felt she couldn’t give her best. And it had to be nothing but the best, most often delivered in one “take” in a pitch-perfect voice pristine as a mountain spring with immaculate diction regardless of dialect. In an era where recordings were conducted “live” (with an eighty-piece orchestra and the singer present) due to primitive equipment, it was a blessing to have an artist who arrived at the studio on time, learnt the song with all its nuances, did one rehearsal and recorded a flawless final version – all in the space of three hours! Composers and budget-conscious producers prized this ability in Lata and Asha.

Rivalries and jealousies are a staple of show business, and often obscure a legend’s lasting contribution to the profession itself. Lata was an early trailblazer: in the 1940s, she pushed for names of playback singers to be printed on records as well as credited on screen when this practice was unheard of. In the early 60s, at the cost of momentarily alienating half her fraternity as well as her foremost duet partner Mohammed Rafi (known to be a simple shy soft-spoken person), Lata fought for the right of singers to receive their fair share of royalties. That was not an easy battle, and she got her way primarily due to her standing and talent. Above all, today’s singers owe a lot to Lata’s efforts for ensuring that all vocalists are treated with respect and are fairly compensated.

Lata ensured that overseas concerts of Indian artists got the dignity they deserved by her insistence upon prestigious venues as opposed to the use of school auditoriums or movie halls, which was the prevailing practice. She was the first Asian vocalist to perform at the Royal Albert Hall in London for three sold-out evenings in 1974, confounding reservations of the venue management who thought it unthinkable that an Indian singer could pack the august arena for even one show. Other singers followed in her footsteps on their overseas tours.

In the early 80s, Lata became very selective about her assignments, at times preferring the privacy afforded by her family holidays overseas to the bustle of Bombay. These prolonged vacations often gave younger singers their lucky breaks in her absence, which Lata never begrudged. Now in her nineties, decorated three times with civilian honours in India (including the coveted Bharat Ratna) as well as other countries, she chooses to live a simple life with her family in a modest apartment on Pedder Road in Bombay that she acquired in 1960. Not much has changed in that home since then, which has the unique distinction of housing India’s first family of music, with five siblings sharing five Padma honours and a history of over twenty thousand melodies that three generations of South Asians grew up with. At the helm of that august clan is Lata Mangeshkar, a towering legend in her lifetime.

Share

Nice one

The most beautiful voice we’ve ever had. Soulful!

Good job Jayang for writing an inspiring and enlightening article on our Legendry Su-Madhur Swar Samragni Lata Mangeshkar.

Beautifully written and brings out the finer nuances of the Legend. Kudos.

Beautifully written and engaging tribute to a veritable Indian institution who stands comfortably above all possible praise.